But exactly what is it telling you? For the most part it is telling you what the wine is, where it comes from and who made it. Have a look at this classic Burgundy wine label for a Savigny-les Beaune 1er Cru ‘Les Peuillets’ from the Domaine Jean-Jacques Girard.

And what is it not telling you? Well perhaps the most important piece of information missing from the label is the grape variety. The Burgundians just expect you to know that, in Burgundy, red is Pinot Noir and white is Chardonnay.

In fact, almost everything of any importance on a Burgundy label presupposes that you already know something about Burgundy. It’s a chicken-and-egg thing which makes newcomers understandably nervous. So allow us to walk you through some Burgundy basics.

Let’s start with the fine print. Look at the label closely. See the mention ‘Appellation Savigny-les-Beaune Controlee’? The most important thing there is the Appellation Contrôlée part. The Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée system (sometimes abbreviated AOC) came into being in the early part of the 20th century as a response to an unregulated and unscrupulous wine trade. The intention was to guarantee the origin of wines and to set some minimum standards.

But in Burgundy, the notion of origin, of where a wine comes from, takes on another dimension. There are 43 winemaking villages in Burgundy, and most of them lay claim to dozens of vineyards known as premier cru (often written 1er Cru). There are 635 1er Cru vineyards officially recognized and so classified in the AOC statutes.

Every label will name the wine by its AOC. But in Burgundy there are a staggering 785 different AOCs! So how do we come to grips with that?

Well, as you have already seen, the AOCs formed themselves naturally into categories (eg, village or premier cru). Understand those categories and you are halfway to understanding a Burgundy label.

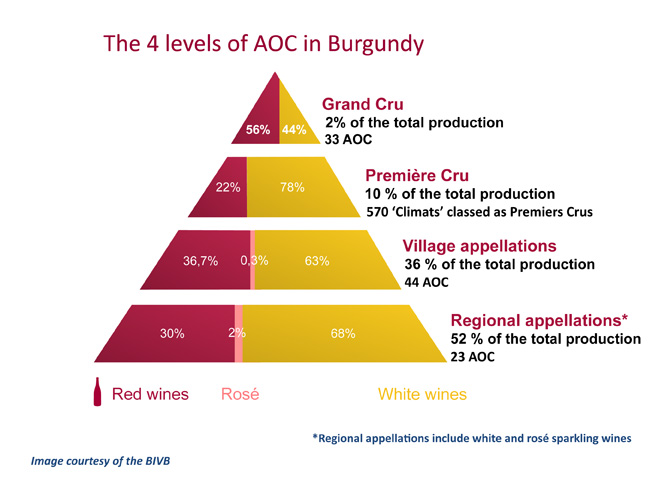

Think of it as a pyramid. There are 4 main categories.

- At the bottom you have the broad regional AOCs. These are called Bourgogne and can be red or white. This is generic Burgundy, and as such, it is possible to blend wines from different parts of Burgundy to make AOC Bourgogne.

- One step higher up the pyramid you have the village AOCs. Straightforward enough. These are wines made entirely from grapes from a specific village.

- Next step up the pyramid are our 635 premier cru. These are vineyards inside a particular village that were classified as exceptional when the AOC s were codified. These wines are named for the village they are found in, followed by the specific vineyard name (as here: the village is Savigny-les Beaune and the 1er cru vineyard is ‘Les Peuillets’).

- And at the top of the pyramid are the crème de la crème, the grand cru. These are vineyards with historical importance, vines that were known well before the AOC regulations came to be. They do not take the name of the village they are in. They stand on their name alone, as in AOC Grand Cru Corton-Charlemagne.

And here it gets tricky. In the last century many Burgundy villages decided that a good way to sell their village AOC wines would be to legally change the name of their town by adding the name of their most famous vineyard. So the village of Gevrey (for instance), hoping to profit from the fame of the grand cru Chambertin, changed its name to Gevrey-Chambertin. But village AOC Gevrey-Chambertin is not at all the same thing as Grand Cru Chambertin. Caveat emptor!

But back to the label. The next thing to notice is perhaps the single most important thing on the label: who made the wine. Traditionally in Burgundy, grapes were grown by farmers who owned the vines. But the wine was made by negociant houses who bought the grapes from the farmers. During the last century however many farmers started making and bottling wine under their own label.

So the label will tell you whether the wine was made by a negociant or by an independent producer. A producer’s label will tell you, at the very least, as here, that Jean-Jacques Girard is a ‘vigneron a Savigny-les Beaune’ (a winemaker in Savigny-les Beaune).

Beyond that, a label can tell you things about the producer or the wine, but none of it is legally binding. You see here that Jean-Jacques Girard wants you to know that this is a ‘Grand Vin de Bourgogne’. But everybody says that! And a claim that wine is made from ‘old vines’ (vieilles vignes) is all relative; there is no legal definition of ‘old vines’.

Which brings us to the crux of the matter. Can you tell from the label if a wine is any good or not? Well, no. You really can’t. A label can essentially tell you two things, 1) where the wine comes from, and 2) who made it. Learn your Burgundy geography and you are on your way to understanding the first. As for the second, that’s more difficult. There are lots of producers, good and bad.

And as Elden Selections has been telling you for nearly two decades, the only way to find good wine is to get to know the producers.